|

Mimi Fariña A biography of the great guitarist, singer, songwriter & humanitarian

|

|

Mimi Fariña A biography of the great guitarist, singer, songwriter & humanitarian

|

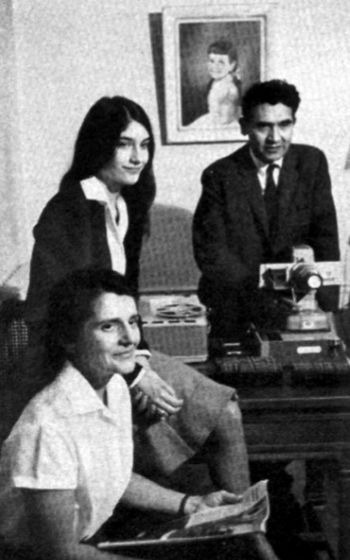

Mimi with her parents, from Time Magazine, Nov. 1962. |

Margarita Mimi Baez was born in Palo Alto, California on April 30, 1945,

the third daughter of Albert and Joan Bridge Baez. The oldest daughter, Pauline,

was six years older than Mimi, and Joan was four years older than Mimi. Both

parents were first-generation

immigrants, her father coming from Mexico and her mother from Scotland. The family

moved frequently while Albert pursued a career

in physics, first as a graduate student then as a professor. They ran a

boarding house for two years while Albert studied at Stanford, then they moved to

Redlands when he took a job as a teaching assistant there.

In 1949 Albert accepted his first professional post as an experimental

physicist at Cornell University in Ithaca, NY. The family moved across the country

to the small town of Clarence Center, halfway between Ithaca and Buffalo. It was

here that Mrs. Baez introduced the family to the Quaker religion and they began attending

meetings at the Religious Society of Friends. Mrs. Baez had no great faith in

organized religion, having attended a Quaker school in her childhood, she felt

that their ethical teachings, specifically their

abnegation of violence, would help guide Albert's struggle with the moral

dilemmas of his chosen field as the United States began developing nuclear weapons.

In 1951 Unesco offered Albert a one-year position in Baghdad teaching physics,

building a laboratory, and initiating research. Off they went to the land

of a Thousand and One Nights. Their year in Baghdad proved to be an unforgettable

ordeal of squalor and poverty and unbearable heat. It was a trial for the entire

family but was particularly

traumatic for Mimi, who was only six at the time. She was placed in a one-room

school of the Catholic Convent with Pauline (Joan was sick with hepatitis and did not have to

attend) and was expected to perform at the level of the older children. Although

she learned to speak Arabic on her own, she had not yet learned to read

and write in English. She was humiliated by a cruel teacher named Sister Rose, who,

Albert Baez believes, choked the joy of reading out of Mimi. It was an immense

relief when his year-long assignment ended the family moved back to California,

though years later they would all agree that the experience had a profound impact

on their lives.

Mrs. Baez compensated for their frequent moving and irregular education by making

sure that, no matter where they lived, Mimi was

always connected to creativity through music or dance lessons. Mimi's earliest

enthusiasm was for dancing. "She learned to dance almost before she learned to walk,"

Joan recalled. All three Baez sisters learned instruments as children. Joan and

Pauline took up the ukelele and Mimi played violin.

In the Spring of 1962 many folksingers happened to be in Paris for an overseas

stomp--there was a brief vogue of expatriatism--so one day in early April they all went on a

picnic together in the countryside and visited

Chartres Cathedral. In attendance were Mimi, her friend Todd Stuart,

John Cooke of the Charles River Valley Boys, English guitarist Alex Campbell,

Texas folksinger Carolyn Hester, and Carolyn's husband Richard Fariña, who

had planned the picnic. Mimi was to learn later that Richard Fariña planned many

picnics, parties, and happenings. He was a writer and poet,

eight years older than Mimi, and like herself, he was half Hispanic

and half Celtic: son of a Cuban father and Irish mother. Handsome, charming, and

learned, Richard dazzled Mimi with stories about the saints and demons depicted in

the Cathedral. Mimi, feeling very sophisticated at sixteen, celebrated with wine

and cigarettes. She got drunk for the first time in her life

and threw her up sandwich on Richard's face. Soon they were in love. Days later,

Fariña sent her a poem, "The Field Near the Cathedral at Chartres," which he had

written about their meeting--though with poetic license he tactfully omitted the

part about Mimi throwing up on his face.

Richard and Carolyn then went to England, since she was scheduled to perform at the

Edinburgh Folk Festival in Scotland. By coincidence, Mimi was also going to England

to visit a Quaker work camp in Newcastle. Richard schemed to get Mimi to Edinburgh

so he could see her again. As the relationship between Richard and Mimi sweetened, his

marriage with Carolyn soured. After the Edinburgh Festival Carolyn returned

to the U.S. and expedited a swift divorce.

Richard and Mimi carried on an epistolary courtship for several months until

both were living in Paris again. In April of 1963, a year after the Chartres picnic,

they were secretly married under

the Napoleonic Code at the courthouse of the First Arrondissement. The witnesses

at the ceremony were Tom Costner and Yves Chaix, friends of Richard.

Later that summer they rejoined the Baez family in California, whereJoan had also

resettled. Protective of their youngest daughter,

the Baezes were suspicious of Richard,

an unemployed "poet" who had dumped one folksinger to marry the sister of another.

But somehow Richard ingratiated himself with the family, either through charm or

sheer determination, and after asking Mr. Baez for his daughter's hand in marriage,

the newlyweds wed once more.

In June of 1964 Nancy Carlen, a friend of Joan, organized a weekend seminar

on "The New Folk Music" at the Esalen Institute in Big Sur.

Celebrations for a Grey Day was finally released in April of 1965. It was a

stunningly original album with poetic lyrics and exuberant instrumentals. That

summer they brought their fresh new sound to the 1965 Newport Folk Festival, where

they rocked the house and won a standing ovation in the pouring rain, just hours before

Bob Dylan's electric set. Though eclipsed in mainstream rock history by

Dylan's controversial performance, the Fariñas' concert became legendary in the

history of the urban folk revival. Years later, Pete Seeger, Theo

Bikel, and many others would remember Richard and Mimi's drenched performance

as a prefiguration of Woodstock, with people taking off

their clothes and dancing in the mud to the ecstatic rhythms of the Fariñas.

Although Richard wrote almost all the songs for the duo, Mimi was noted for her

creative style of guitar playing, which danced nimbly around Richard's

percussive attack on the dulcimer. Even Joan, an excellent guitarist herself,

acknowledged in her autobiography And a Voice to Sing With that Mimi was

the better guitarist. Elektra producer Jac Holzman recalled Mimi as "hypnotic

and immensely musical." Rick Turner of Acoustic Guitar magazine described

Mimi's guitar playing as "innovative," "fully formed and very original,"

"sophisticated and driving." Mimi learned much of her technique while living in Paris

and hanging out by the Seine River listening to French and Algerian street singers.

She also learned a great deal from Bruce Langhorne: "We were both highly influenced

by the guitar of Bruce Langhorne," she said.

"His whole concept of rhythm added a vitality that we wouldn't have had otherwise."

Nevertheless, Mimi forged her own distinctive style. She developed a version of the

Travis style with a thumb pick and two fingers, and employed unusual combinations

of strums and arpeggios, smoothly integrated into the flow of the music. She also

used modal tunings that created a strange alchemy with the diatonic structure of

the dulcimer. Yet her style

was somewhat self-effacing, never calling attention to itself but rather

complementing and blending with the dulcimer. Perhaps Richard said it best when he

described the dreamy, evocative style of her playing as "weaving modal memories."

David Hajdu, in an interview with Fresh Air, emphasized the importance of Mimi's influence

upon Richard:

Richard and Mimi released a second album, Reflections in a Crystal Wind, in

December of 1965, on which Mimi contributed her first

original composition, "Miles," a shimmering instrumental dedicated to Miles Davis.

In February of 1966 they made an appearance on

Pete Seeger's Rainbow Quest TV show. It would be the first of many film

appearances for Mimi, but at the time she seemed a bit shy in her brief

conversations with Seeger. Nevertheless, they played splendidly and created such

infectious rhythms that Seeger was inspired to jump in with a pair of maracas.

Seeger was clearly moved by the duo and predicted that

their eclectic style would soon be influential all over the world.

Mimi stayed with The Committee for about a year. She later regarded them as

"my own little

grieving group." The description is revealing: despite all the activity and

experimentation, her fling with the psychedelic scene, and her

optimism in the press, this was still a difficult period of adjustment as Mimi

struggled with her career and her public image.

There was also talk of recording a solo album with Vanguard. This may have been

to fulfill a contract, as Vanguard typically signed their artists for three albums,

and she and Richard had only recorded two. The album was to be called Quiet Joys,

and Mimi recorded a couple of Richard's songs that they had not recorded before he

died--"Quiet Joys of Brotherhood" and "Morgan the Pirate." But the solo album never

emerged, for reasons unknown. What finally appeared in April of 1968 was

Memories, a gathering of live recordings,

studio outtakes, and singles, plus the two solo tracks mentioned above. Despite the pell-mell format, it was a fine collection

of songs that reaffirmed the duo's artistic reputation. However, it also affirmed Mimi's

role as a tragic figure. The cover featured Jim Marshall's lovely photo of

Mimi standing alone in a field. She smiles ever so slightly, and yet her eyes are

infinitely sad. It was a powerful image that resonated

with fans for years to come: Mimi, alone, tragic, as if her duty heretofore were

to mourn the death of Richard, like a Madonna statue that sheds everlasting

tears. Mimi came to resent the image--"the sad-eyed widow bit,"

as she called it.

Another unwelcome contribution to this image was the song "Meagan's Gypsy Eyes"

on Blood, Sweat & Tears' first album, Child is Father to the Man,

released in February of 1968. The song was written by Steve Katz, with whom Mimi

had had a relationship about a year before. They had met in December of 1966, when Katz

was with his first group, The Blues Project, playing at The Matrix in San Francisco.

"I wound up staying with her for a couple of weeks before going

back to New York," Katz recalled, "and Mimi eventually came to stay with me."

The relationship didn't last long, but one outcome of it was the "Meagan's

Gypsy Eyes," which Katz wrote and recorded when the Blues Project evolved into

Blood, Sweat & Tears. "I was very young and very much in love, and when Mimi

left me, I went through the typical romantic withdrawal routine:

hurt, self-pity, anger, reconstruction. 'Meagan's Gypsy Eyes', unfortunately was

written and recorded during the angry period." The lyrics are indeed spiteful:

Folk Duo, Part Deux

We might guess, judging from Jans' subsequent career, that he was interested in going

in a more mainstream direction as a rock artist. But it is also likely that he was

tired of laboring under the shadow of the legendary Richard Fariña. A 1972 interview

suggests the uneasy relationship Tom had with his predecessor:

Mimi, on the other hand, struggled against commercialism. She began to record a solo album

with CBS Records, which reportedly cost $10,000 to make, but she was turned off by

the bottom-line priorities of

the music industry. Her producer said to her, "Just tell me you want to have a hit and

we can work together." She recalled in an interview years later,

More Than a Marginal Act

A few years later, Mimi recorded a demo for the Cambridge folk label Rounder

Records. Rounder rejected the demo at first, but by the

mid-eighties there was a resurgence of interest in the folkie generation, as

evidenced by the restoration of the Newport Folk Festival in 1985 (the first since

1969). No doubt many people were turned off by the decadence of MTV and sought

the palpable humanity of a more home-spun music. At any rate, Rounder Records became

interested in Mimi again. She began recording around June of 1985,

and Solo was released at the end of the year. In her "Mimi Sez" column of

the Bread & Roses newsletter she explained her album thus:

The lure of the stage remains compelling. For me it's not the glamour of show

biz so much as a marvelous means with which to communicate. A song can relate

emotions which

reach the poet in all of us, and can tap a common ground we often forget to tread.

It's those feelings that inspire me to write and sing."

In the late nineties, after years of hard work and a flotilla of honors and

awards for her achievements, Mimi began to plan her retirement, and launched a

three-million dollar funding campaign that would ensure Bread & Roses' enduring

legacy. But in November of 1999, following a bout with Hepatitis C, Mimi was

diagnosed with neuroendocrine cancer. She had no choice but to take an early

retirement to begin chemotherapy as well as alternative healing approaches. She

was still able to participate in a gala 25th anniversary celebration in March of

2000, fearlessly appearing with a scarf wrapped around her head, the unmistakable

sign of her condition. "I don't have bad hair days anymore," she joked, "I have bad scarf

days."

Mimi struggled on for another year and a half, sought alternative medicine in

Switzerland, all to no avail. In June of 2001 an article appeared in the San

Francisco Chronicle, "friends are asking everyone to pray for a miracle."

No miracle came. Mimi died in the quiet morning of July 18, 2001, at

her hilltop cottage in Mill Valley.

Mimi Fariña forged a purposeful life out of senseless

tragedy, and her legacy lives on in the work of Bread & Roses and the

people who have been touched by her music.

--Douglas Cooke

"I was good at the violin and I was a good dancer and I knew it....Which was such

a relief from feeling incompetent. When I danced or played music I could be who I

really was."

After Joan graduated high school in 1958, Albert took a position at Massachusetts

Institute of Technology, so the family moved east again and settled in Belmont, a

suburb near Cambridge. Pauline was already on the east coast attending Drew

University in New Jersey. Mimi entered Belmont High School, and Joan enrolled in

Boston University's School of Drama, where she met Debbie Green.

Debbie was an accomplished guitarist and performed at the Cafe Yana once a week for

five dollars. She taught both Joan and Mimi, who had each dropped their old

instruments for the guitar. Both sisters began to explore the collegiate coffeehouse

scene, where the Folk Music Revival was brewing, and befriended Eric von Schmidt,

John Cooke, Geno Foreman, and other legends in the making.

Mimi recalled in Baby, Let Me Follow You Down, a collective memoir

of the Cambridge folk scene,

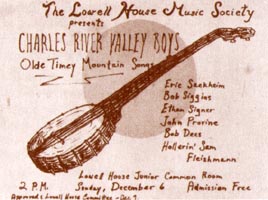

"I know precisely the moment when I

got drawn into wanting to play folk music. I was thirteen. I got a call from Joanie

who was at Harvard Square. I was at home and she said, 'Get on a bus and get down here.

There's a group here I know you'll enjoy.' It was the Charles River Valley Boys

at Lowell House in one of their first times playing."

Abandoning her studies, Joan soaked up the traditional Appalachian

ballads and began performing at the local coffee houses: Club 47, The Ballad Room,

and the Golden Vanity.

Joan had always been the natural performer of the family,

entertaining friends with her quick wit and talent for mimickry and winning school

prizes for her ukelele performances. In Cambridge she continued to seek the stage,

and quickly gained a reputation for her angelic soprano. Her voice and image somehow

managed to be both earthy and ethereal at once, ideally suited to the tragic and

spooky mountain ballads she sang. Although Joan occasionally invited Mimi to join her

for a duet at some of her gigs, the rising star was clearly Joan. The Baez family

watched in amazement as Joan gained one impressive victory after another: she filled

the Cambridge coffeehouses, outgrew them in a year, sang with Odetta and Bob Gibson at the Gate

of Horn in Chicago, and performed for an audience of thousands at the first

Newport Folk Festival in 1959. In November of 1960 Joan crowned this series of

victories with an album released by Vanguard Recording Society. The younger sister

was astonished, awe-struck, eclipsed.

Dazzling Stranger

In 1961 Albert accepted another assignment from Unesco, to lead their

Division of Science Teaching in Paris. Off they went to Paris, Mr. and Mrs. Baez

and Mimi. Pauline had married, and Joan had her singing

career, so only Mimi still lived with her parents. In Paris she all but gave up public

education and was finishing up high school through correspondence courses, which

left her time to enjoy Paris. She starred in an experimental film by Peter

Robinson, a friend of her father, and the soundtrack was recorded

by Rolf Cahn, a guitarist they knew from Cambridge. She also continued to study

dance, and even toured with a ballet troupe in Germany.

Richard Fariña at the Troubadour

Photo by Alison Chapman McLean

Photo by

Young girl, you chose the amber coil of a wish,

unlocked it with the cocking of a heel

and stepped away. While in the lunge of flight

I know the tale in your dark body's book.

Mimi and Richard moved in a one-room cabin near Joan's home in Carmel Valley.

Richard worked on his novel during the day, and at night they would entertain

themselves by making music. They began composing songs based

on a unique, polyrythmic and improvisational interplay of guitar and dulcimer, an

unusual combination that opened up

unknown musical territory as wild and beautiful as the Carmel countryside.

No doubt their music drew its uniqueness from the extensive travelling they had

done individually, each being exposed to a diversity of styles that gave

them an eclectic sophistication uncommon in American folk artists of the day.

Although their collaboration began only for their own entertainment, their sound was

so unique and infectious that everyone encouraged them to share it with the world.

Richard began writing lyrics, and Joan submitted some of them to Vanguard's

publishing company, Ryerson, who offered him a publishing contract.

Carmel Valley, CA

"Well, any time you found Joan Baez, Richard and Mimi Fariña, and me in the same

place there had to be singing, so instead of meetings and lectures, sing we did,

in the sulphur baths, on the lawns, even during meals sitting at long wooden tables

in the lodge. Sunday afternoon we invited the neighborhood in general to join us,

turned the deck of the Esalen swimming pool into a stage, and sang to everyone."

Thus Nancy Carlen describes the first Big Sur Folk Festival. It was here that

Mimi and Dick Fariña debuted as a folk duo, playing the only three songs they had

practiced well enough to perform in public. But their short set was a hit: the

audience begged for more, and three different record companies, including folk

giants Vanguard and Elektra, offered them recording contracts. Since Richard

already had a publishing contract with Vanguard, they signed with Vanguard, which

had done so well for Joan.

That fall Mimi and Dick recorded their first album in Olmstead Studios in Manhattan,

with the aid of studio sessionman Bruce Langhorne, a guitar wizard and multi-instrumentalist

whom Richard had befriended during the recording of Carolyn Hester's album two

years earlier. Mimi and Dick were considering going back to Europe after recording

the album, but instead they moved to Cambridge, where each of them had lived before.

They rejoined old friends and met newcomers to the still growing

folk boom--Eric Andersen, Tom Rush, Paul Arnoldi, and others. Mimi and Dick, newcomers

themselves as a performing duo, began to play the myriad folk houses, The Rook, the Loft,

Club 47. But even among the increasing competition of the Cambridge scene, their

music rang out its unique charm, and they won several categories in the

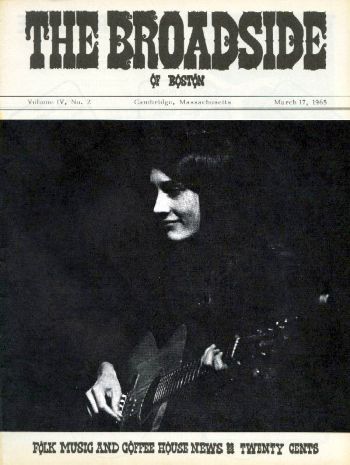

Broadside of Boston annual readers poll.

Broadside of Boston, March 17, 1965

"She contributed mightily to his development as a

musician, and if it weren't for Mimi and her knowledge

of music theory and her understanding of chords and

her own creativity Richard Fariña would never have

emerged a half-decent songwriter as he did, he would

never have had a moderately successful career as half

of a performing folk duo as he did with Mimi."

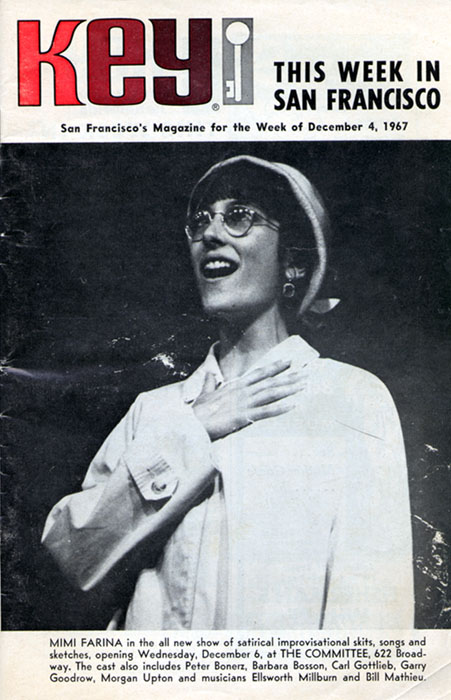

Late in 1967 Mimi joined an improvisational comedy troupe, The Committee. Founded

by Alan Myerson and Irene Riordan, who had been members of the Second City comedy

troupe in Chicago, The Committee was based in San Francisco and lasted from 1963

to 1973. Key Magazine described their act as "ingeniously clever barbed wit and satirical lampooning of

sacred cows, fetishes, political issues and timely topics." Mimi started as a fan

in The Committee's audience, but then,

Mimi performs a skit with

The Committee

"I laughed so hard they asked me

to join them.... Dick loved the Committee and I think I was testing being him, as

if I had gained some of his energy when he died. I just thought, 'This is what I'm

supposed to be doing now.'"

Through The Committee Mimi made many friends, some of whom she

would remained connected to for years to come: Julia Payne, with whom she toured

briefly (there is a short clip of them playing together in Celebration at Big

Sur); Chris Ross, to whom she later dedicated the song "Reach Out;" and several

others who later dedicated their time to Bread & Roses, such as Carl Gottlieb,

Gary Goodrow, and David Ogden Steirs (later of M*A*S*H fame).

"Death that clouds her life will be forever

I do not know whether Mimi ever heard the song, but if she did she must have

perceived the references to her: the similarity of "Meagan" and "Mimi" and a host

of other personal allusions would have made it obvious. It was yet another

contribution to the hagiography of Mimi as the perpetual widow.

She is loved yet cannot love, not never."

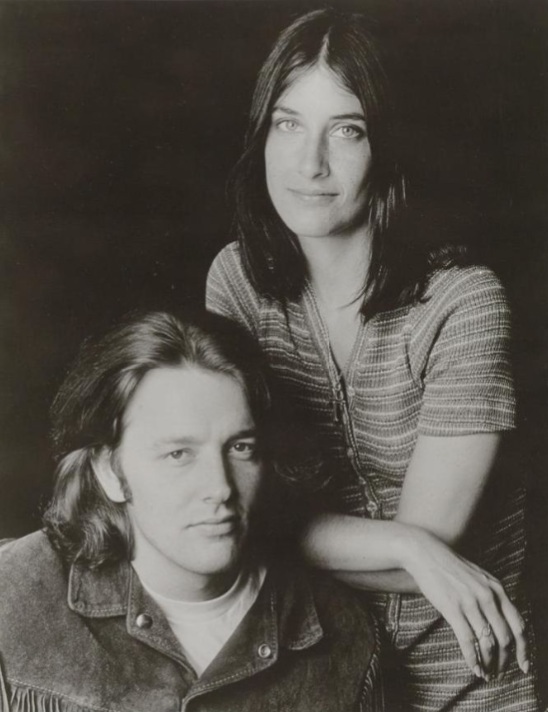

In 1970 Joan introduced Mimi to an aspiring singer-songwriter named

Tom Jans. Both had been writing songs and looking for a partner to perform with.

They first experimented as a trio including Julie Payne, with whom Mimi had

been performing. But Julie then decided to spend all her time acting, and Mimi

and Tom struck out as a duo. As luck would have it, they blended beautifully as

musicians and singers. As Tom reported in an interview,

In 1970 Joan introduced Mimi to an aspiring singer-songwriter named

Tom Jans. Both had been writing songs and looking for a partner to perform with.

They first experimented as a trio including Julie Payne, with whom Mimi had

been performing. But Julie then decided to spend all her time acting, and Mimi

and Tom struck out as a duo. As luck would have it, they blended beautifully as

musicians and singers. As Tom reported in an interview,

"I was singing by myself

in California, and Mimi was looking for someone to sing with.... I was singing

at a little club, and some people from the Institute of Nonviolence asked me to

come up and have dinner. That's when I met Joan and through Joan I met Mimi...

Mimi and I just started

singing, just at home kind of singing for friends, and suddenly...we were getting

calls from clubs--so we worked out a couple of songs."

Their first gig was at The Matrix in San Francisco, but their appearance at the

Big Sur Festival was regarded as their formal debut.

They signed with a relatively new independent label, A&M Records, whither Joan

had migrated after her ten-year run with Vanguard. Mimi and Tom recorded a

splendid

album, Take Heart, which included her most famous song, "In The

Quiet Morning," a requiem for Janis Joplin. Many feel that Take Heart features

some of Mimi's finest work. Mimi and Tom toured extensively in the United States and

Europe, and appeared on the Dick Cavett Show. They were a class act--

great singers and great guitarists who blended well and even wrote songs together.

But around May or June of 1972 they split up, for reasons never clearly documented.

"I don't think I've ever listened to an entire Dick and Mimi Fariña album...

I guess I resent the whole thing sometimes." "I don't feel that

way at all," said Mimi, staring intently at Tom. "Well, I'm not related to him,"

said Jans in a restrained way. "I mean he's not my brother or anything."

As if the challenge of living up to Dick's larger-than-life persona were not

daunting enough to begin with, Tom's partnership with Mimi also coincided with

something of a Richard Fariña Revival. During 1971, the year of Mimi and Tom's

debut, Vanguard released The Best of Mimi &

Richard Fariña; Paramount released a film adaptation of Been Down So Long It Looks Like Up

To Me; and a musical celebrating his life and art, Richard Fariña: Long

Time Coming and a Long Time Gone, ran in Boston and New York. Mimi herself was

involved with

the musical, collaborating with Joan, Judy Collins, and Richard's father. There

were even plans for Mimi and Mr. Farina to write a biography of Richard. Amid all

this attention to a deceased

legend, it's not surprising that Tom Jans felt the need to strike out on his own, lest the

shadow that seemed to loom over Mimi should overtake him as well. Tom released a

solo album of thoughtful rock music with A&M in 1974, and a few more albums

followed on Columbia in a fairly successful career.

"For me, that was an example of how somebody didn't treat someone else like a

human. I was looked on as a product.... I told him that I'd love to hear myself on

the radio, but it's not the aim of my life. I don't think they wanted me. They

wanted something they could package. If things got really difficult I don't know how far I would bend. I've got to make a

living. But this time I wouldn't bend far enough."

In the end, Mimi was released from her contract and the album disappeared into

oblivion. Or, as she good-humoredly described it, "I was released and the album

wasn't." Mimi salvaged a couple of the songs she had written, and recorded them

again with Joan for her 1973 album,

Where Are You Now, My Son? But the irony could not have been lost on Mimi:

Joan had the freedom to record her most controversial album ever, while Mimi's

career was faltering. The CBS memo releasing Mimi from her contract

had described her as "a marginal act," a label that enraged Mimi for years

to come. She became increasingly bitter about the music industry. With the growth

of the "arena rock" phenomenon in the early seventies, record companies began

to cast their greedy

eyes on bigger and bigger profits, squeezing out "smaller" artists and turning

rock stars into rich moguls who became disconnected

from their fans, their community, and their roots.

The valiant work of Bread & Roses occupied most of Mimi's time from 1974

onwards, though she continue to appeared at folk festivals and made guest appearances

on various albums by friends of hers. But she never entirely let go of an ambition to validate herself

as a solo performer with a solo album.

By the late seventies Bread & Roses had earned Mimi a reputation independent of

Richard Fariña, Tom Jans, or her big

sister Joan. She had made a name for herself, and with renewed confidence she

started shopping around for a record contract again. She recorded an album for

Wolfgang, a label led by Bill Graham. An article in

CoEvolution Quarterly in 1978 announced

that it would be out in September under the title More Than A Charitable Act.

Unfortunately, the album never materialized, for reasons unknown.

The valiant work of Bread & Roses occupied most of Mimi's time from 1974

onwards, though she continue to appeared at folk festivals and made guest appearances

on various albums by friends of hers. But she never entirely let go of an ambition to validate herself

as a solo performer with a solo album.

By the late seventies Bread & Roses had earned Mimi a reputation independent of

Richard Fariña, Tom Jans, or her big

sister Joan. She had made a name for herself, and with renewed confidence she

started shopping around for a record contract again. She recorded an album for

Wolfgang, a label led by Bill Graham. An article in

CoEvolution Quarterly in 1978 announced

that it would be out in September under the title More Than A Charitable Act.

Unfortunately, the album never materialized, for reasons unknown.

"After many years of putting my music career in second place and choosing to devote

most of my time to the non-profit world, I am pleased to announce that soon I will

be releasing my first solo album. No, I won't be leaving Bread & Roses; it still brings

joy and purpose to the lives of many, including my own. But I do intend to share

more of my time between music and what Tom Paxton refers to as one's "day gig".

An office structure provides a stability for me that is often missing in an

entertainer's lifestyle. But don't misunderstand: I'd never refuse a limo ride, or

a standing ovation.

Mimi toured extensively in the mid-eighties but seems to have stopped around 1988.

She must have realized at some point that Bread & Roses was her true calling, her

life's work. In retrospect it seems as if her entire life uniquely prepared her for

this mission: her Quaker upbringing, her parents' politics, her

early experiences as a young child in Baghdad, which inspired her passion for

social justice; her constant moving, which gave her a distaste for travel and a

fondness for the creature comforts of home; her deeply conflicted feelings toward

the musician's life, which bred her cynicism for the industry yet also a fervent

belief in music's healing power. Perhaps the most determining factor of all was her role

as the youngest daughter in the family. Perhaps I am biased because I too am the

youngest child, but it seems to me that her little-sister relationship with Joan

patterned her relationship with Richard and to a lesser extent her entire approach

to life. She never sought fame, had no interest in it; and yet Joan Baez and

Richard Fariña were the dazzling sun and mysterious moon that brought such

strange and ironic experiences upon her. The unique path she walked

deepened her compassion for the marginalized, the outcast, the left behind, and sparked a

desire to make their world a little brighter.

farinaweb@yahoo.com

Mimi in 1984, photo by Tom Strickland

Back to Mimi's page.

Back to the Richard & Mimi Fariña homepage.