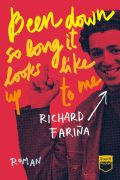

Been Down So Long It Looks Like Up To Me

New York: Random House, April 28, 1966.

Click on covers for larger images and more info.

Click here for reviews and literary criticism.

"I been down so long, seem like up to me,

Gal of mine got a heart like a rock in the sea."

--Furry Lewis, "Turn Your Money Green"

(adapted by Eric von Schmidt as "Stick With Me, Baby"

on the album Dick Fariña & Eric von Schmidt)

THIS NOVEL WAS DECODED WITH...

THE CAPTAIN MIDNIGHT

CODE-O-GRAPH

and escape from Reality.

An interpretation by

Douglas Cooke,

licensed Fariña nut

Published April 28, 1966, two days before Fariña died in a motorcycle

accident, Been Down So Long It Looks Like Up To Me became a cult favorite

among fans of his music and eventually attracted the attention of a more literary

readership through Fariña's association with Thomas Pynchon, who wrote a blurb

for the novel.

Fariña had mentioned Pynchon in the notes for his song "V." on Celebrations

for a Grey Day and also in his 1963 essay, "Monterey Fair," published in

Mademoiselle (March 1964). But Fariña was known for his name-dropping,

and cover blurbs are often commercially motivated. It wasn't

until the publication of Pynchon's gargantuan novel, Gravity's

Rainbow, (1973) that people began to consider a significant literary connection between the

two writers. That formidable brick of a book, which many regard as the most

important novel of the latter half of the 20th century,

was "Dedicated to Richard Fariña," and that tribute alone makes Been Down

So Long worthy of literary study.

In time Pynchon and Fariña came to be regard as part of a "Cornell School" of

writers, which included David Shetzline (author of the "ecological" novel,

Heckletooth 3, and DeFord, which was also dedicated to Fariña), and

M.F. Beal (author of Angel Dance, a detective

story with a Chicana lesbian investigator). Gene

Bluestein discerns three preoccupations that characterize the Cornell school:

"political paranoia (the idea of a Big Brother state), despair over the

destruction of the environment, and an awareness of the special impact on the

American mind of all levels of popular culture." (1)

The most famous author associated with Cornell was of course Vladimir Nabokov,

one of the great writers of this century, who taught at

Cornell in the late fifties while Pynchon and Fariña were students there.

Robert Scholes later recalled Fariña's enthusiasm for the great novelist:

i.) Background: The "Cornell School"

"About thirty years ago when I was a graduate student at Cornell, I was

standing in the hall of the building one day. A young man, an undergraduate

who was aspiring to be a writer at that time, came up to me. He had a book

in his hand, and he grabbed me and said, "you've got to hear this, you've

go to listen to this." He opened the book, and he started to read. "Lo-li-ta,

trippingly on the tongue," and he went on and read me the first several

paragraphs of Lolita. This young man, whose name was Richard Fariña,

became a writer and wrote a book called Been Down So Long It Looks Like

Up To Me." (2)

It was Leslie Feidler, the ornery and iconoclastic literary critic, who first

applied the architectural term "postmodern" to literature. He once explained

the term thus:

ii.) The Quest for the Real

Been Down So Long It Looks

Like Up To Me is the tale of a world-weary traveler who has been on

a voyage and seen many horrors and has returned a changed man, like the

blue-eyed son in Dylan's "A Hard Rain's A-Gonna Fall." But while the blue-eyed

son returns galvanized, ready to proselytize,

determined to confront the injustices he has seen, Fariña's character,

Gnossos Pappadopoulis, is reluctant to talk about

what he has seen. Like the taciturn heroes of Hemingway's fiction, he is

morally paralyzed by his experiences and now seeks only alleviation and escape.

Fariña's model for Gnossos is Odysseus, weary veteran of

the Trojan War, the prototypal anti-hero, the original draft-dodger, who

cares not for glory but just wants to go home. Gnossos' first mission in

the novel is to find a home, an apartment. The lyrical overture of the novel

is awash in allusions to The Odyssey. The entire novel,

especially the geographical names of this fictional college town (based on

Ithaca in Upstate New York, home of Cornell Univesity and of course namesake

of Odysseus's island), is littered with absurd classical allusions: we hear of Harpy

Creek, Dryad Road, the Plato Pit (a restaurant), Circe Hall (a women's dorm)

, Hector Ramrod Hall, Minotaur Hall, Labyrinth Hall, etc. Even Gnossos's

ridiculous name is oddly allusive. Does it refer to Knossos, the

Mediterranean island, home to the city of Crete, where the minotaur roamed

the labyrinth? (At one point we are told that Gnossos

"bellowed like a Cretan bull." (165)) (4) The name may

also allude to the Greek word for "knowledge." The root is "gno", cognate

with the English "know," and it yields the verb "gign sko," (to know) and

the nouns, "gn sis" (knowledge), "gn stes" (one who knows), and "an gnosis"

(recognition), often used as a literary term to refer to recognition scenes

in drama.

Gnossos is one who has gained a painful knowledge from his travels but has

not yet learned to use it: his knowledge has not been transubstantiated into

wisdom. As with the absurdly named college halls and roads, some essence from

the past has been lost, cheapened, commodified, scrambled into the

kaleidoscopic alphabet soup of pop culture. Another of the academic halls is

called "Anagram Hall" (52) which appropriately symbolizes the loss of

meaning in the jumble of modern life. Later in the novel we will meet G.

Alonso Oeuf, the mastermind behind Gnossos' downfall, who splutters phrases

in a half-dozen languages. But behind his pseudo-sophistication lies nothing

but clich s; he too represents the fallen state of the modern

world. Like Kurtz sprawled on his stretcher in Conrad's Heart of

Darkness ("all Europe contributed to the making of Mr. Kurtz"),

Oeuf seems a

conglomeration of enervated cultures, the weary terminal of history, an

ailing, infirm, meaningless scrapheap of allusions rotting in postmodern

squalor.

Gnossos' quest is to find the meaning behind the easy

allusions. In the late fifties there arose among among youth a yearning

for meaning, substance, roots, authenticity. Authenticity above all

was idealized by young discontents. It was, in

varying degrees, a catalyst of the Beat movement,

the Blues Revival, and the back-to-land communes and pastoral pilgrimages of

the Hippie movement. But it was a particular fetish of the urban folk revival.

In Positively 4th Street,

David Hajdu explains the appeal of folk music among college students

in the late fifties by noting that it coincided with the invention of

plastic: folk music "put a premium on naturalness and authenticity during

a boom in man-made materials, especially plastics." It was "a music that

glorified in the unique and the weird,

challenged conformity and celebrated regionalism during the rise of mass

media, national brands, and interstate travel." (5)

Been Down So Long It Looks Like Up To Me is set mainly in 1958, when

the folk music revival was just warming up (the Kingston Trio

scored a hit that year with the badman ballad "Tom Dooley").

But aside from the guitars, dulcimers and autoharps at house of Grun, a friend

of Gnossos, most of the musical references are to the jazz of the Beatniks.

In one scene, however, Gnossos plays Mose Allison's 1957

album, Back Country Suite, a country-blues and jazz fusion. As Mose Allison

blends the two genres,

Gnossos falls somewhere between the two movements. His outward rhythm is the

syncopated beat of jazz, but his inner song is the lonesome highway of folk.

He shares with both the beats and the folkies a contempt for the bourgeois,

the superficial, the mass-marketed.

Yet even Gnossos, for all his polymath learning, makes constant allusions to

Plastic Man, Captain Marvel, the Green Lantern, and other

comic book heroes. (6) He also identifies himself

with--and sometimes poses as--various figures throughout history: Montezuma

(22), Dracula, Prometheus (91), the Holy Ghost (171), Ravi Shankar (171),

Winnie the Pooh. He is a keeper of the flame, a seeker of the Holy Grail. He is

the antecedent of the character in Joni Mitchell's anthem, "Woodstock," who

says, "I don't know who I am, but life is for learning." Gnossos himself

realizes that he has "too many roles to play" (25).

Significantly, Gnossos'

favorite superhero is Plastic Man, who could stretch himself into any shape.

Plastic Man seems to have been a favorite of Fariña's as well;

he mentioned him in his essay "The Writer as Cameraman." (Mimi, in the

notes to Long Time Coming and a Long Time Gone, explained the

reference thus:

"As for Plasticman, Dick just loved all that weirdness, all that

cartoon-craziness; he really had that great sense of mush! I have an odd

feeling that they've met by now, he and Plasticman and all the rest.

I hope they're having a good laugh.") (7)

Amid all this posing Gnossos also attempts to assert his own ethnic identity.

His Greek heritage provides him a link to the archetypal, the mythic,

something enduring to prop up amid the littered postmodern world. Yet this

self-assertion of identity often takes mundane forms. His rucksack, that Jungian

baggage of his identity, holds sundry tokens of his Greek heritage: dolma

leaves, Greek wine, and mouldy goat cheese. The silver dollars are also

assertions of the Real, the Authentic, the true coin of the realm rather than paper

representations thereof. Explaining his use of silver dollars to Dean

Magnolia, he warns of "parasitic corruption that gets spread through the

handling of dollar bills." (54) When a cashier questions the silver dollars,

Gnossos claims that he is Montezuma and threatens to tear out her heart and

eat it raw. More posing, more delusions of heroic grandeur, the assertion of

an ancient archetype to muscle out the present, the ephemeral, the corrupt,

the artificial. All this is represented by the cashier "smelling of purchased

secrets from Woolworth's, lips puckered, passion plucked or pissed away

some twenty years before. The resigned are my foes." (22)

Gnossos has a similarly

arrogant attitude to a platinum-haired girl working in a drugstore.

"Deaf to her doom," he imagines, and ascribes another pathetic narrative to

her life:

Like his alternating identities, the Greek food and the silver dollars are

tumbled together in the rucksack with tokens of childhood fantasy, such as

rabbits' feet ("Placate all the gods and demons, finger in every mystical

pie" (114)) and the Captain Midnight Code-O-Graph, which loses a spring at a

significant moment in the story. When Gnossos learns that he has been partly

responsible for the death of Simon, a fellow student who killed himself upon

learning that his girlfriend was in love with Gnossos (who had seduced her

in an earlier chapter), he experiences what may be the silliest epiphany in

all literature:

iii.) The Deathwish

Am I reading too much into the contents of the rucksack? Perhaps. But this

epiphany is similar to another in a short story of Fariña's called "The

End of a Young Man," in which an American visiting Ireland assists in the

bombing of a patrol boat, then finds out that there had been people on board.

The young man's discovery that he was responsible for the death of another

person brings an end

to innocence and youth, just as Gnossos undergoes a fall from innocence,

here symbolized by the "boing" of the Code-O-Graph.

Carolyn Hester, in an interview with Richie Unterberger in Urban Spacemen

and Wayfaring Strangers,

(8) reveals that Fariña actually had such an adventure in Ireland,

where he was tricked by the IRA into believing that there would be no

people aboard the boat he was to bomb. Carolyn Hester makes no reference to

the short story, but she believes that Fariña was deeply affected by that

experience, and she felt that it explained much of his subsequent behavior.

Mimi Fariña also discussed Fariña's morbidity in the notes to Long Time

Coming and a Long Time Gone. Death haunts Fariña's music as well.

The song "Raven Girl," which his liner

notes describe as a deathwish, may reflect his guilt over the bombing of the

boat.

Perhaps this deathwish attracted Fariña to Michelangelo's poem,

"Sleep." Fariña quotes this poem both in Been Down So Long and in the short story

"The Good

Fortune of Stone." In the short story he quotes the poem in the original

Italian:

But sanity for Gnossos would lie somewhere between the untroubled,

patly-defined life of Gunsmoke junkies and

the nervous energy of the perpetually moving target. Gnossos' deathwish is

a yearning for quiescence, for the quelling of his conscience. The

impossibility of this yearning gives him a contempt for those who have some

modicum of peace in life, those who are "deaf to their own doom." In the

song, "Sell-Out Agitation Waltz," Fariña scorns such people

"who ain't aware that every

morning they wake up dead." And yet death is his own secret wish;

he hovers

between cherished life and longed-for death: "Sweet mortality, I love to

tease your scythe." (169)

Herein lies the protagonist's central conflict. He went in quest of something

Real, but he

has found and seen things of such terrifying reality that he needs to numb

himself. He anesthetizes himself through drugs, through his posture of

coolness, through masquerading as superheroes and other heroic figures of

myth and history, and most significantly through his declaration of Exemption.

iv.) Exemption

The delusion of exemption derives from some harrowing experiences in Gnossos'

travels. He almost died in the frozen snow of the Adirondacks while pursuing

a wolf; he witnessed an atom bomb explosion in Las Vegas; and watched someone

being tortured by pachucos in New Mexico. His escape from the

dangers he experienced has given him, at a conscious level, a belief that he

is exempt:

It is with relief that we watch Gnossos finally relinquish the rucksack, in

his usual ritualistic way, at the grave of Heffalump in Cuba. The rite of passage

into manhood seems long overdue, after his pre-novel travels, the death of

Simon, his brush with the clap, and the death of Heffalump. There are perhaps

too many mini-resolutions in the novel, too many epiphanies, too many karmic

adjustments rather than one big,

cathartic, aesthetically satisfying climax, and along the way we have to put up

with too much of Gnossos' posing and pointless partying. As a result, many

critics have overlooked the complexity and significance of the novel altogether,

dismissing it as an outdated effort now useful only as a document of its time.

A Village Voice review of Hajdu's Positively 4th Street claimed

that the novel's "sole surviving virtue is as an early case study in hip male

chauvinism."(10)

v.) Layers

I suspect Fariña did want his novel to be, like Fitzgerald's novels of the

twenties, a classic representation of the age that formed him. His fault,

then, lay not in being oblivious to the chauvinisms and flaws of Gnossos and

his age but in spending too much time creating the scene before leaving it.

After all, the epigraph to the novel is a quote from Benjamin Franklin, "I

must soon quit the scene," which Fariña pulled out of Lord knows where.

Clearly Been Down So Long was intended to be a bildungsroman,

a coming of age novel,

and not just a party novel. As a document of its time, Been Down

So Long does not succeed quite as well as The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test,

which, though taking place five or six years later, has many interesting

parallels with Fariña's novel.(11)

There are many other themes in this complex

novel that I have not even addressed here, and many aspects that I still

do not understand, many allusions to pop culture, literature, science, and math

that I just don't get. Furthermore, there is reason to believe that despite

the years that Fariña devoted to writing and revising the novel, it never

became a fully-realized expression. Mimi observed in an interview with

Patrick Morrow that the composition of the

novel spanned two continents and two marriages. (12)

I will add to this that it was begun in the author's obscurity, when he craved

recognition (in the same interview Mimi said, "It's hard to feel great

when you're not being acknowledged at the time."), and it was finished when Fariña had achieved

the extraordinary success of two critically-acclaimed albums. Most first

novels are uneven, revealing imperfectly blended layers of experience, but

Fariña's was more uneven than most, begun, according to his own legend, a

few minutes after quitting his role as a blind harmonica player huckstering on

the streets of France, and completed by a respected musician acclaimed by

Pete Seeger and Jean Ritchie.

By his own admission, Fariña was still in the

process of "resolving the conflict between Inside and Outside," which he

describes as Gnossos' role as well, in an article written a few days before

he died. (13) A further complication in the novel's

genesis is that one of its major innovations, the use of illustrations to

portray episodes that would only be alluded to in the text itself, was rejected

by the publisher.

The editor at Liveright Publishing who rejected William Faulkner's

third novel, Flags in the Dust, told the young author, "The trouble is

that you had about 6 books in here. Your were trying to write them all at

once." (14)

This, I believe, is one of the problems with Fariña's confusing novel, the

outcome of two marriages, two continents, two careers, and God knows how many

conceptions of what the novel would be. But

when reading the first few novels of Faulkner we have the

more successfully executed genius of later novels to cast a clearer light on

the tentative, gestating ideas of the earlier work.

With Fariña we do not have that advantage. Guessing at his literary potential from

his novel is a bit like predicting

Judy Collins believed that Fariña was just beginning to

show a greater awareness of himself in the months before he died, and Joan

Baez's tribute to him implies the same. (15)

Just as his potential was incalcuable, so must

the more shadowy nooks of his novel remain unfathomable.

Douglas Cooke

For further criticism on this novel, see the

Literary Criticism

page.

1.) Bluestein, Gene. "Tangled Vines." (a review of Thomas

Pynchon's Vineland.) The Progressive. June 1990, Vol. 54, issue 6,

p. 42-3.

I'll try to say for the last time why I invented this term to begin with. I

thought it was a strategy that could be used in the field of literature,

just as it had been used earlier in the field of architecture, where people

had made it clear that the golden arches of McDonald's were to be taken quite

as seriously as any high-flown, high-blown attempt at building a new building."

(3)

Like Nabokov and Pynchon, Fariña gathers the trappings of contemporary American

life in all its tawdry plastic commercialism, forging from the materials of pop

culture a common language between

himself and his contemporary audience to tell a tale of high

seriousness through low humor. And like so many of the novels of Nabokov and Pynchon, Fariña's

novel is a quest.

See her in a year, straddling some pump-jockey in the front seat of a '46

Ford, knocked up. Watching Gunsmoke in their underwear, cans of Black Label,

cross-eyed kid screaming in a smelly crib. Ech. Immunity not granted to all.

As in the Montezuma scene, Gnossos requires heroic posing to assert

his superiority over her: explaining his use of bath oil, he says, "Ancient

custom is all, balm for warrior, makes you good to feel, right?" (171)

...while roaming the streets in a hopeless attempt to pace away an oily

guilt, to purge the accusing picture of Simon sucking an exhaust pipe, he

looked into his rucksack for a vial of paregoric to soothe his agitated

nerves. But instead he found the Code-O-Graph, neatly sprung in two where it

had been sitting, with all innocence of inanimate purpose, in a bed of

rabbit's feet. While he was turning it over in his hands it discharged its

secret little Captain Midnight spring with a boing, shuddered, and lay

lifeless forever. (110)

The passage has a number of remarkable parallels that nag at Gnossos'

conscience. Gnossos' craving for an opium-laced cigarette to smoke

corresponds to the image of Simon sucking on an exhaust pipe; one is an

unconscious mimickry of the other. The reference to "oily guilt" recalls an

earlier scene where Monsignor Putti comes to deliver Extreme Unction but

instead anoints Gnossos' feet in a "lovely sacrament," explaining that

one's feet "carry one to sin." (50) Yet now Gnossos seeks to "pace away" his guilt

by "roaming the streets," and he finds the epiphany of his lost innocence in

"a bed of rabbit's feet." (110) The themes of escape and guilt, futile

cautionary superstitions and reckless behavior are so inextricable linked that

they seem to hound each other in an eternal, hellish circle.

The sand that inches from the tide

Was Fariña haunted by the whispers of the dead? Like Tennyson's Ulysses,

who lost so many of his companions at sea, and in old age found that "the deep moans round

with many voices," perhaps Fariña was tormented by the memory of the men

killed on the boat.

Will claim the steps I sow,

The whispers in the ocean deep

shall pick my weary bones.

Caro m' il sonno e pi l'esser di sasso

In Been Down So Long, Gnossos translates part of the poem into English at a

frat party:

Mentre che'l danno e la vergogna dura,

Non veder, non sentir, m' gran ventura;

Per non me destar, deh! parla basso.(9)

"Dear to me is sleep...While evil and shame endure, not to see, not to feel

is my good fortune." (30)

Here is a translation of the entire passage:

"Dear to me is sleep, and dearer to be made of stone

The story "The Good Fortune of Stone" is another version of the wolf

story told in the novel. Pynchon states in his 1983 introduction to the novel

that Fariña told this story many times. The near-death experience recounted

in both versions of the wolf story must have touched him

profoundly, and this, combined with his feeling of guilt (vergogna),

may

have given him the conflicting impulses of a deathwish and a feeling of

exemption, two impulses which, it seems to me, are never entirely resolved

or sorted out from each other in the novel. Not that everything needs be

resolved; art is not there for us to simply decode or "figure out." The

broken Code-O-Graph puts an end to the easy answers of childhood, and

Gnossos too ridicules such patness. When Pamela says, "Must you be so

cryptic?" Gnossos thinks to himself, "Always present a moving target,"

and answers sarcastically, "Define a thing and you can dispense with it,

right?" (39)

While evil and shame endure,

Not to see, not to feel, is to me a good fortune,

Therefore do not wake me. Shh! Speak softly."I've been on a voyage, old sport, a kind of quest, I've seen

fire and pestilence, symptoms of a great disease. I'm exempt. (15)

His friend Calvin Blacknesse had warned him of "the

paradoxical snares of exemption." (56) It is a rationalization or perhaps

an inversion of a deeper, unresolved fear. Like victims of post-traumatic

stress disorder who imagine that they are Jesus Christ, Gnossos embraces

his delusion of exemption as a way of protecting himself from further harm.

Like Fariña, Gnossos is haunted by a pandemonium of phobias. He fears demons,

monkeys, all manner of bad omens which he seeks to avert by superstitious

rituals, such as the Mediterranean apotropaic ritual of clutching the testes.

When he sees the monkey in the loft, he clutches "his groin to hex away the

dangers of the underworld." (131) These are not the actions of one who truly

believes he is immune from death. Exemption is a defense, a mantra "I am not ionized and I possess not

valence" (12)), an apotropaic trinket, a superpower to save the day.

Brooklyn, 2001.

FOOTNOTES:

Return to essay.

2.) Coover, Robert, et al. "Nothing But Darkness and

Talk? Writers' Symposium on Traditional Values and Iconoclastic Fiction."

Critique. Summer, 1990, vol. 31, issue 4, p. 233ff.

Return to essay.

3.) Ibid.

Return to essay.

4.)

Fariña, Richard. Been Down So Long It Looks Like Up

To Me. New York: Random House, 1983. The Randon house and Penguin paperbacks

are both reprints of the original Random House edition, but the Dell paperback

was an entirely different typeset. Therefore, the page numbers in

this essay will apply to all but the Dell paperbacks.

Return to essay.

5.) Hajdu, David. Positively 4th Street: The Lives and

Times of Joan Baez, Bob Dylan, Mimi Baez Fariña, and Richard Fariña.

New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2001. Pages 10-11.

Return to

essay.

6.) When Fariña was writing the book in the early sixties,

comic books were just beginning to gain an older audience, as Stan Lee,

editor and head writer of Marvel Comics, created a new generation of more

realistic superheroes who had real-life problems, neuroses, and foibles.

In The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, published two

years after Fariña's novel, Tom Wolfe also observes the frequent

identification with comic book heroes, and their leotarded images began

appearing on album covers around this time. However, Fariña's novel takes

place in 1958, and Stan Lee's first experiments with the new comic book hero,

The Fantastic Four, did not arrive until 1961.

Return to

essay.

7.) Quoted in Fariña, Richard. Long Time Coming and a Long Time

Gone. New York: Random House. p. 40 (p. 36 of the Dell paperback). Mr. Fantastic, the Stan Lee creation

who had the same stretchy power, debuted in 1961, before the novel takes

place.

Return to essay.

8.) Unterberger, Richie. Urban Spacemen and Wayfaring

Strangers: Overlooked Innovators and Eccentric Visionaries of '60s Rock.

San Francisco: Miller Freeman Books, 2000.

Return to essay.

9.) Fariña, Richard. "The Good Fortune of Stone." Reprinted

in Long Time Coming and a Long Time Gone, p. 161 (p. 151 of the Dell

paperback).

Return to essay.

10.) Robert Christgau, "Folking Around," Village Voice,

June 26, 2001, p. 79.

Return to essay.

11.) Been Down shares many themes with The Electric

Kool-Aid Acid Test: the preoccupation with drugs, sex, superheroes, the

countercultural distrust of "the Establishment." Gnossos' urge to depart from society, conflicting

with his awareness that one always has to return to that society,

finds its parallel in the dilemma of the Merry Tricksters: no matter what heights

of discovery one reached through acid, one always had to return to earth,

one always had to come down. Kesey never fulfilled his determination to "go

beyond acid" because society's pruderies got to him first and put him in jail.

Likewise, Gnossos' petty pranks earlier in the novel eventually get him

busted, and he is sent into the army. In both books the Establishment prevails

over counterculture enlightenment. The theme of exemption also arises

in Electric Kool-Aid; see page 35 of the Bantam edition.

Return to essay.

12.) Morrow, Patrick. "Interview with Mimi Fariña."

Popular Music and Society, vol. 2, no. 1, Fall 1972. This interview is

available on this website. Click here.

Return to essay.

13.) "The Writer as Cameraman." Long Time Coming and a

Long Time Gone," p. 41-42.

Return to essay.

14.) Blotner, Joseph. Faulkner: A Biography. Revised

one-volume edition. New York: Vintage, 1991. p. 223.

Return to essay.

15.) Collins, Judy. The Judy Collins Songbook.

New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1969. p. 185; and Baez, Joan. Daybreak.

New York: Dial Press, June, 1969. p. 135-136. I quote Judy Collins:

"I've always thought that Richard was just breaking through into some greater

perception of himself and other people when he died. He knew there was someone

at home inside his wildly imaginative head, and he was starting to come into

contact with it, to let it out."

Return to essay.